TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILROAD

Transcontinental Railroad

A Historical Outlook on its Construction

The building of the Transcontinental Railroad in the 1860s is a story that heralds the courage and innovation of the construction companies and workers who built it.

In the mid-1820s the first steam-powered railroad lines, such the Baltimore & Ohio or the Mohawk & Hudson, had just begun to offer passenger and freight service. The contractors and construction companies who built the railroads were already aspiring to bigger and better things. At the time, Eastern railroads were seeking a way to cross the Allegheny Mountains and reach Ohio or the Great Lakes. Pioneering spirits wanted to figure out how to build a railroad that would cross the American continent.

One such pioneer was Asa Whitney, a New York tea merchant who began to promote the idea of a transcontinental railroad in 1844 after returning from China. Fully aware of the benefits such a railroad promised for trade with China and East India, Whitney declared his intention to build a railroad from Lake Michigan through the South Pass to the Pacific, backed with a land grant 60 miles wide along the length of the road.

Whitney brought his proposal to Congress in 1848, but it was voted down due to its unrealistic construction scheme. Another, better-prepared proposition was presented to Congress in 1850 and again in 1851, but it failed to earn sufficient support because of conflicting interests between the Northern and Southern states. The Southern states were opposed to the project altogether. Whitney then turned to the English government and proposed a similar plan for a transcontinental railroad through Canada. This attempt failed as well.

Asa Whitney ran out of money and finally gave up his campaign in 1852. However, his dream of the Pacific Railroad stayed alive. The discovery of gold in California not only created the market for the first important transcontinental traffic, it also significantly changed the public attitude towards the West. The West was no longer considered a wasteland of mountains and plains. It was seen as the land of opportunity. Scores of people wanted to travel beyond the Mississippi, through the territories that stretched to the Pacific Coast.

Asa Whitney ran out of money and finally gave up his campaign in 1852. However, his dream of the Pacific Railroad stayed alive. The discovery of gold in California not only created the market for the first important transcontinental traffic, it also significantly changed the public attitude towards the West. The West was no longer considered a wasteland of mountains and plains. It was seen as the land of opportunity. Scores of people wanted to travel beyond the Mississippi, through the territories that stretched to the Pacific Coast.

In 1853, Congress passed an act providing for the survey of possible railroad lines from the Mississippi to the Pacific. At least five routes were surveyed, and each received support from a different sector. Unfortunately, the multitude of diverse interests among the supporters and an increasing rift between the North and the South rendered agreement on a route impossible.

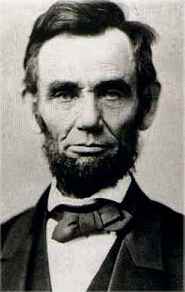

In 1860, Republican Abraham Lincoln won election to the White House on an anti-slavery ticket. His election almost immediately caused the longstanding rift between the North and the South to intensify, and very shortly thereafter the Southern states followed South Carolina into secession. The violent conflict that would later be known as the Secession War, or the American Civil War, had begun.

However, with the Southern states out of the picture the major antagonism to the transcontinental railroad was gone, and both the Senate and House of Representatives were able to pass the Pacific Railroad Acts of 1862 and 1864. These laws granted rights of way and use of building materials along the way, a 20-million-acre land grant and government support for loans of 60 million dollars to companies that would build the transcontinental railroad and its feeder lines. Those companies included:

- the Union Pacific Railroad, to be built from the Platte River Valley in Nebraska to the border between Nevada and California, with two feeder lines from Omaha and Sioux City;

- the Central Pacific Railroad, to be built as a feeder line from Sacramento over the Sierra Nevada to meet the Union Pacific eastwards and to San Francisco in the West;

- and the Leavenworth, Pawnee & Western, later to be known as the Union Pacific Eastern Division, which was to link the 100th meridian Southeast with Kansas City.

The charters awarded to the railroads provided rights of way and use of stone and timber to build the roadbed, and granted 6,400 acres of land for each mile of railroad built. Based on the estimates made after the surveys, the government agreed to provide nearly half the needed capital for the project, about 60 million dollars. More than 50 million dollars would have to be raised from private investors.

Construction Begins, 1863

The Central Pacific broke ground in Sacramento, California in January, 1863. The Union Pacific broke ground at the Missouri River bluffs near Omaha, Nebraska in December, 1863. A competition arose between the construction crews of the two railroads, to see who could finish first.

The Central Pacific broke ground in Sacramento, California in January, 1863. The Union Pacific broke ground at the Missouri River bluffs near Omaha, Nebraska in December, 1863. A competition arose between the construction crews of the two railroads, to see who could finish first.

In December 1862, the Central Pacific Railroad awarded its first construction contract to Charles Crocker & Company. The construction company subcontracted the first 18 miles to firms with hands-on experience, and the Central Pacific reached Newcastle, California on June 4, 1864. From that point on, it was a long haul up the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

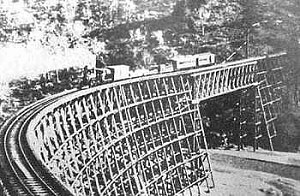

The physical construction of the rail line was a job with an enormous scope, and it was often a painfully slow process. There was also constant pressure to meet time or geographical deadlines. The construction crews had to cut grade, build snowsheds, blast through hard rock and lay track through snow. Deep fills, switchback routes, high trestles, huge rock cuts and fifteen tunnels were necessary to make it over the Sierras.

To create this rail line, an enormous amount of tools, materials and supplies were required. Each mile of track required 100 tons of rail, about 2,500 ties and two or three tons of spikes and fish plates (metal pieces that joined the rails and prevented climatic expansion and contraction of the metal). Some of the tools needed included wheelbarrows, horse drawn scrapers, two-wheel dump carts, shovels, axes, crowbars, blasting powder, quarry tools and iron rods. On top of that, locomotives, wheel trucks, switch mechanisms and foundry tools were needed as well.

Providing these supplies was no small challenge. All supplies for the Central Pacific came from the East, and the Panama Canal shortcut did not exist at that time. All material, rails, rolling stock and machinery was shipped around Cape Horn on the southernmost tip of South America, en route to California. River steamers then took the material upriver to Sacramento, where it was offloaded to platform cars and hauled up into the mountains. If a shipment didn't leave the East Coast on time (and this happened frequently) or if an accident occurred in the shipping, the resulting delay could create a great hardship. The contractors often cut corners, spiking only seven of every ten rails or allowing other shoddy work along the line.

In 1865, the construction company faced another shortage, a labor shortage. They hired Chinese workers against the wishes of the other laborers and their foreman, but when the first group proved to be efficient and hardworking, the contractor recruited more from California and China itself. It was the Chinese men and their back-breaking labor that would get the railroad through the Sierra Nevada.

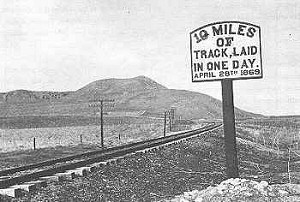

While the Central Pacific crews were struggling through the mountains, they heard tales of the speed with which the Union Pacific crews were able to work. As they grew closer to the point where the two railroads would meet, the Central Pacific crews decided they had something to prove. Spurred on by their supervisors, on April 28, 1869 they laid an extraordinary ten miles of track across the Utah desert between sunrise and sunset. They used 25,800 ties, 3,520 rails, 55,000 spikes and 7,040 fishplates. The Irish and Chinese crews worked together and completed the ten mile stretch in 12 hours. This feat has never duplicated by human beings in railroad construction since. It also brought the Central Pacific rail within ten miles of the Union Pacific line, ensuring the Union Pacific could not hope to replicate the achievement.

While the Central Pacific crews were struggling through the mountains, they heard tales of the speed with which the Union Pacific crews were able to work. As they grew closer to the point where the two railroads would meet, the Central Pacific crews decided they had something to prove. Spurred on by their supervisors, on April 28, 1869 they laid an extraordinary ten miles of track across the Utah desert between sunrise and sunset. They used 25,800 ties, 3,520 rails, 55,000 spikes and 7,040 fishplates. The Irish and Chinese crews worked together and completed the ten mile stretch in 12 hours. This feat has never duplicated by human beings in railroad construction since. It also brought the Central Pacific rail within ten miles of the Union Pacific line, ensuring the Union Pacific could not hope to replicate the achievement.

Led by construction superintendent Samuel B. Reed, chief engineer Grenville M. Dodge and contractors John S. and Dan T. Casement, the task facing Union Pacific construction crews was relatively easy at first. Their route went largely through flat plains, following the Oregon Trail through the Platte Valley, then crossing the Continental Divide through the Black Hills in Wyoming.

While the terrain was comparatively easy to work in, Union Pacific construction crews faced one problem that their Central Pacific rivals didn't: Indians. In Nebraska, the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes continually harassed Union Pacific construction crews. Forts were established along the line to protect the railroad. When the workers weren't at work or asleep, they were at war with rifles at their sides, ready for the next Indian attack. Sometimes the Indians fought the workers; other times, they damaged the progress made by the construction crews. In August 1867 at Plum Creek, Nebraska, Cheyennes pried up some rails and caused the derailment of a freight train. The train crashed and the Indians looted the cars.

The Union Pacific's construction materials were sailed up the Missouri or brought in by wagon. Their biggest difficulty lay in getting railroad ties, since there were few natural trees as were found in the Sierras. They had to import the ties until the Chicago & Western railroad line was extended to reach the Black Hills of Wyoming and the Wasatch Mountains of Utah.

Both companies laid track essentially the same way. They sent crews far ahead to do a preliminary survey, then location surveys. The graders would grade 100 miles of track at a time. In the mountains they graded as much as 200 to 300 miles at a time since the actual building took so much longer. Bridge, culvert and trestle crews worked five to 20 miles ahead. Then the tracklayers came in, grabbing rails out of horse-drawn carts. Then came the men to pound in the spikes. At the end of each line was a base camp that supplied material and food to the workers. As construction of the line was completed every 100 to 200 miles, the base camp would move up to keep in proximity to the crews.

Construction Finished With a Single Word: "Done"

As the two companies approached the Promontory Mountains in Utah, both realized there was only one route through. Blasting began on both sides to lay track. The east slope was more difficult as the grade was steeper. On both sides, fills and trestles were necessary for crossing deep ravines. Finally on April 9, the Union Pacific, and on April 11, the Central Pacific, stopped trying to lay tracks ahead. Congress established that they would meet at Promontory Summit.

As the two companies approached the Promontory Mountains in Utah, both realized there was only one route through. Blasting began on both sides to lay track. The east slope was more difficult as the grade was steeper. On both sides, fills and trestles were necessary for crossing deep ravines. Finally on April 9, the Union Pacific, and on April 11, the Central Pacific, stopped trying to lay tracks ahead. Congress established that they would meet at Promontory Summit.

By April 16, 1869 the two crews were only 50 miles apart. The Union Pacific crew was delayed because it ran out of ties. They also had to build three more trestles to make the summit.

May 8 was the target date for the union of the two railroads. On May 7, the two lines were just 2,500 feet apart. Former California Governor Leland Stanford traveled to Utah along with other officials from California and Nevada, bringing two golden spikes with him. One was made by David Hewes, one of the Central Pacific's largest supply contractors. The other was sent by The San Francisco "News Letter." West Evans, the contractor who supplied most of the Central Pacific ties, hand-polished and waxed a special last tie made out of laurelwood. The Pacific Union Express Company sent a silver plated sledge for the final blow.

The Union Pacific team was not prepared by May 8. Many of the dignitaries traveling on their end got held up by weather or by labor disputes. However, on May 9 the Union Pacific laid the final 2,500 feet of track, leaving one length of rail separation. The two trains from the east arrived the morning of May 10th.

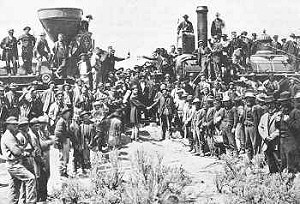

At noon on May 10, 1869 a ceremony began with approximately 600 people in attendance. The two engines, the Central Pacific's Jupiter and the Union Pacific's No. 119, stood cowcatcher to cowcatcher at each end of the last rail.

At 12:20 p.m., one official from each railroad joined together to lay in the ceremonial last tie using the gold spikes. The silver sledgehammer was used to "drive" the spikes, but not enough to damage them. (The real final tie, spike and sledge were ordinary.) The two trains were then driven together, and a bottle of champagne was broken over the laurel tie. A telegraph went out across the nation with the simple message: "Done." The transcontinental railroad was complete. At that instant in Promontory Point, Utah, coast-to-coast travel time was reduced from four to six months to six days. In just seven years, the Union Pacific railroad had built 1,086 miles of railroad lines from Omaha, Nebraska. The Central Pacific had built 690 miles from Sacramento, California. Both railroads had crossed a major mountain range, the Rocky Mountains in the East and the Sierra Nevada in the west.

While the Transcontintental Railroad was started in the midst of a war that divided America, its completion marked a new unity and connection between the east and west coasts that further defined the United States as a single nation. The railroad signaled the death knell for the "western frontier" as it made possible the large-scale immigration to, agricultural and other trade with, and ultimately the industrialization of the western U.S.